Designing a better village community

The ingenious and thoughtful design is derived from Zhang's thorough understanding of the village over the years.

"I first came to Xiwusutu more than 40 years ago as an architecture student doing fieldwork," says Zhang, now a professor at the Inner Mongolia University of Technology and chief architect of Inner Mongolian Grand Architecture Design.

"What struck me were the apricot trees, the narrow lanes following the land's slope, and the quiet sense of history. Years later, when young artists began settling here and called me back, I saw the village with new eyes," recalls the architect in his 60s.

When the local government launched the Beautiful Village vitalization campaign several years ago, Zhang and his team were invited to help enhance the public spaces and improve building performance.

A new structure wasn't initially part of the plan. "But as we spoke with villagers and artists from cities, two strong desires emerged," Zhang explains.

"The villagers wanted a place to gather, celebrate, and hold events. The artists dreamed of a gallery, a workshop, an incubator — a space where they could create and connect."

Despite the lack of complete funding for the construction, the government offered something just as valuable: a plot of land in the village center, which was once home to a temple and later a production brigade headquarters, with two 200-year-old trees still draped with red prayer ribbons in a corner.

"It was not only the geographic heart of the village, but it also held an emotional and spiritual core," Zhang notes.

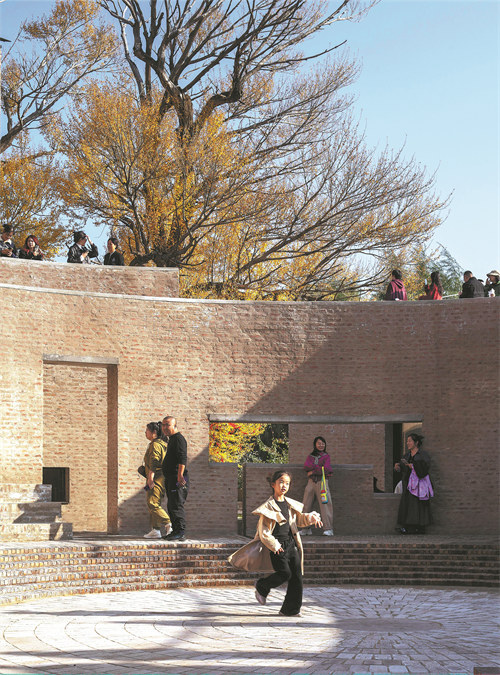

What followed was a collaborative effort. Villagers and artists pooled together the initial funds. The government provided leftover bricks from village renovations. Zhang's team contributed the design, construction oversight, and, most challenging of all, facilitation among all stakeholders.

"The hardest part was not in drawing the plans, but reconciling wishes, constraints, and resources into a shared vision," Zhang emphasizes.

He describes the project through four core ideas — reused bricks, passive climate response, spirituality, and what he calls a "low-build".

Zhang insisted on "zero construction waste" and collected old bricks from demolished homes for reuse.

The imperfect, irregular bricks were woven into the new structure using an innovative bricklaying technique developed specifically for local laborers to lower the technical thresholds.

Rather than hiding their irregularities behind plaster, the team celebrated the textures of time.

Heating and cooling are major challenges in Inner Mongolia's climate. Zhang integrated a passive ventilation system that draws cool air from underground tunnels and releases warmth through solar chimneys.

"We wanted a building that costs almost nothing to run," he says.

The two old trees become the soul of the project, as the structure wraps around them, framing sight lines and creating gathering spots under their canopy.

One of Zhang's most innovative concepts — the "low-build" — means pursuing high quality through low cost, low carbon, and low-tech tolerance, Zhang explains.

Imperfection was allowed, as masons didn't have to achieve millimeter precision; welded lines didn't have to be perfectly straight. "We prioritized spatial experience over technical perfection, and sometimes the 'errors' made the space more alive," Zhang says.

Since its completion in 2023, the community center has become a catalyst, drawing many young urban visitors on the weekends. Village life has been simultaneously enriched. Elderly residents play chess in the courtyard, children chase each other through open corridors, and artists host exhibitions that draw crowds even during winter.